The Philadelphia Orchestra’s announcement final winter that its former music director Riccardo Muti would return in late October 2024 to steer Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem raised a number of expectations. Muti’s private authority is itself a number of, from his lifelong Verdi advocacy to his championship of public help of the humanities as nationwide heritage: a polemic he has usually engaged in at surprising moments from the pit itself. In 2004 he based the Luigi Cherubini Youth Orchestra, which pulls gamers from throughout Italy; in 2015 he based the Riccardo Muti Italian Opera Academy on the Teatro Alighieri in Ravenna.

He made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 1972 and served as its music director from 1980 to 1992, succeeding Eugene Ormandy. He was welcomed final weekend to its not too long ago named Marian Anderson Corridor as a returning hero. For Philadelphia, it had change into clear that in October 2024 and ten days earlier than the presidential election, expectations and nerves could be in a state of great agitation together with probably the most extroverted side of the nice work itself and past even its most fulminous musical identification—that’s to say for its plea for the destiny and salvation of the nation itself.

Verdi’s Messa da Requiem was premiered in Milan in 1874 on the primary anniversary of the loss of life of the octogenarian Alessandro Manzoni, creator within the 1820s of I promessi sposi [The Betrothed] and the foremost literary voice of the Risorgimento. He had been appointed senator by King Vittorio Emmanuele II in 1860 following the primary wave of Italian unification. As a novelist and statesman, Manzoni is doubly credited with the making of Italian consciousness, and that primarily via the notice and use of a nationwide language. A local of Milan, Manzoni cultivated the pluralistic vernacular of Dante Alighieri and the linguistic, dramatic sweep of the latter’s early fourteenth-century Divine Comedy. Verdi, one would possibly argue, did the identical in music.

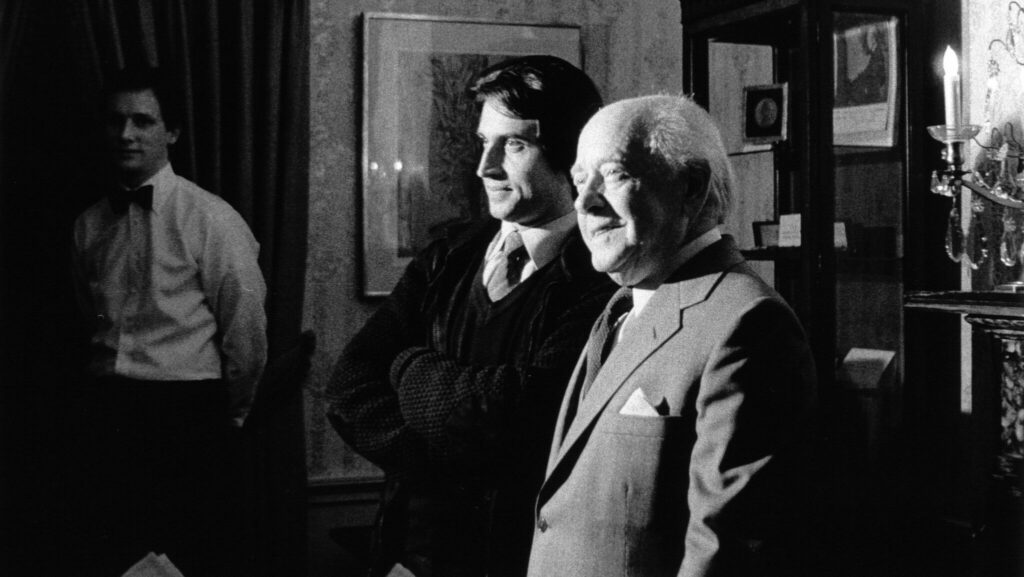

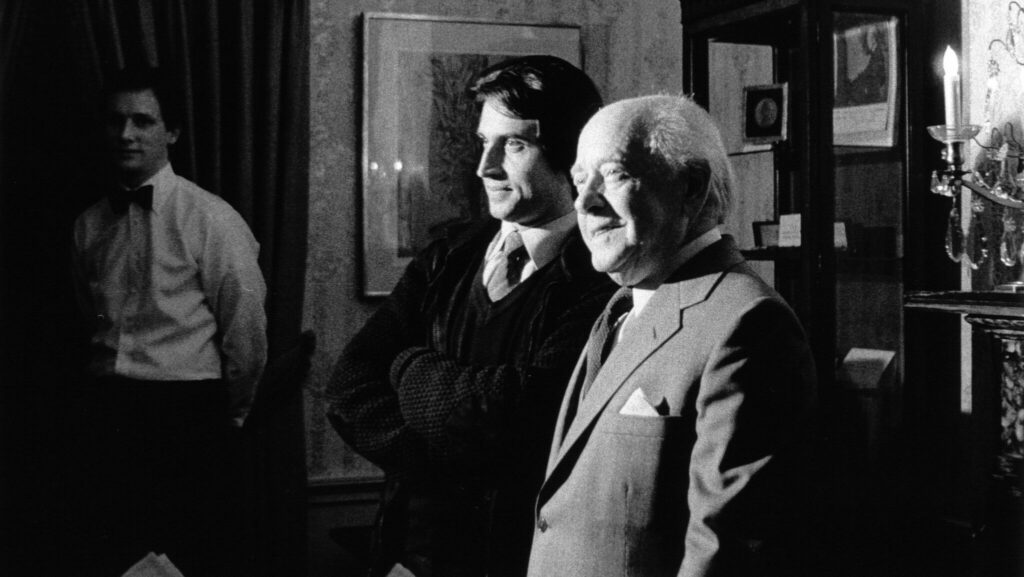

Louis Hood

I owe a lot of my very own training as a listener to this nice to work to Riccardo Muti. I heard my first reside efficiency at Florence’s Maggio Musicale in 1981, once more at La Scala in 1987. The latter efficiency was recorded reside and have become a cornerstone of my early CD library. In 2024 at age 83, Muti retains the identical energized however distinctly austere conducting persona that I recall from 1981. This isn’t an opera, he appears to be reminding his viewers, in implicit rebuttal to Hans von Bülow’s well-known however transcendentally inane declare that the Verdi Requiem quantities to an opera in clerical garb (“eine Oper im Kirchengewande”).

Like Manzoni and Dante earlier than him, Verdi was an anti-clerical and anti-papal Catholic. The Requiem erupts from that legacy right into a sustained and infrequently stunning depth. It speaks within the constantly double voice of the person and the collective, the “I” and the “we.” This duality it attracts from Dante and the foundational double voice that opens the Divina Commedia:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita,

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura…[At the midpoint of our life,

I found myself in a dark wood…]

The rapid change from the surprising first-person plural to the singular has an uncanny impact. It creates an ambiguity, a form of forcefield, between particular person and the group or polity. The dominant pronoun of the Requiem textual content is singular: Salva me, Libera me, Save me, free me. We’re born alone and face loss of life alone. The phrases are intoned alternately each by the soloists and the refrain, in different phrases functionally and acoustically alternating between particular person and collective utterances. We’re born and die alone however face political disaster as a polity. However who speaks via this collective voice of the Verdi Requiem?

Some years in the past, I wrote an essay in regards to the surprising return of the Requiem mass within the secular late-nineteenth-century live performance corridor (Brahms, Dvorak, Verdi) and known as the phenomenon “the voice of the individuals in the intervening time of the nation.” (I quote from Listening to Motive: Tradition, Subjectivity, and Nineteenth Century Music, Princeton College Press, 2004.) I stand by that description. Verdi brings an awesome pressure and energy to the Requiem—a method with a excessive dose of brass and noise that led a French artwork historian to match it to that of the large-scale educational late nineteenth-century painters generally known as the pompiers or firemen.

There’s something distinctly unembarrassing about Verdi’s consequence, nonetheless. And that unembarrassing high quality has to do with the interior resistance to ideological posturing. The voice that speaks for the individuals doesn’t routinely communicate for the nation. The posturing and violence of nationalism are resisted, disavowed. And that resistance has one other dimension, which can be so apparent as to be counterintuitive. The collective, choral voice of the Requiem assembles and speaks in music alone; exterior the work and its efficiency, this voice doesn’t exist. It has nothing to do with the collective voice as carried out, for instance, in a political rally. Its aesthetic structure resists each ideology and violence.

In 2024, this argument requires some updating. The favored, collective voice I had in thoughts resists what at the moment we seek advice from as populism. Twenty years again, populism was not a burning political difficulty and definitely not a poisonous one. At present it’s a dominant class and the cipher of an ideology that claims to serve the individuals however in truth does little of the sort. Quite, populism is a politics of emotion and manipulation, enjoying on resentment and infrequently on rage, and serving a plutocracy possessed by a particular contempt for the individuals and their variety. Populism is an power and never a regime. Because the political scientist Nadia Urbinati has argued, populism is a pre-governmental power. If and with regards to energy, it both backtracks to democratic processes (equivalent to elections) or metastasizes into fascism.

In 1982, the director brothers Paolo and Vittorio Taviani positioned the Requiem’s Hostias – the middle of the Offertory part of the requiem textual content— on the emotional and dramatic core of their masterpiece The Night time of the Capturing Stars [La notte di San Lorenzo]. The movie is in regards to the persistence of fascism through the interval of political vacuum between the autumn of Mussolini in 1943 and the tip of the Second World Warfare in 1945. It’s thus about the potential for common survival and renewal impartial of the nation and its centrifugal ideological pressures.

The setting is a Tuscan city known as San Martino in August 1944, when the German occupation and native fascist authorities are each disintegrating with convulsive violence and the Individuals are because of arrive. The city has been focused by the Germans for destruction following the killing of a German soldier. The townspeople take refuge of their church, which is then bombed in an act of mixed German treachery and Italian cuckolding. These inside are killed or maimed. The Hostias is heard in the intervening time of the explosion. It’s heard for a second time because the inhabitants who’ve survived by hiding within the woods resolve to tackle self-chosen pseudonyms as an act of strategic disguise (they’re becoming a member of the partisans and want codenames) and symbolic rebirth. One younger man, who had beforehand sung the Hostias in church, chooses for himself the identify “Requiem.” This ritual self-naming is just not undertaken within the identify of both religion or nation. It’s moderately a second of rebirth as an providing to the longer term.

Fascism can’t be resisted within the identify of the nation when the nation has recast itself – and the thought of itself– within the identify of fascism.

It could be pure projection on my half to have felt the aura of the political second as a dimension of the particular depth that Muti and the Philadelphia Orchestra dropped at the Requiem Saturday, October 26. A political aura in each time and area: ten days earlier than the 2024 presidential election and a couple of mile from Structure Corridor. Nowadays, the sheer sound of this orchestra produces a uncommon degree of drama and depth. The fabled fantastic thing about its string sound is retained and matched to a Chicago Symphony-level of pressure within the brass and percussion. The cellos on Saturday gave the impression to be weeping in despair, whereas the double basses produced probably the most ferocious pizzicato I’ve ever heard.

The soloists, all 4 comparatively younger, have labored with Muti in Ravenna and elsewhere. Soprano Angela Meade produced a transparent and exact tone that exudes youthfulness, however with a sound that inflates simply to a powerful override of the orchestra, particularly within the Libera me. Isabel De Paoli often pressured her sound for supplementary quantity and appeared to fulfill the non- or anti-operatic exigencies with a decided lack of vibrato. Giovanni Sala sang the Hostias with a form of understated perfection. Maharram Huseynovmixed an interesting lyricism will a seamless vocal vary and notably fluid low tones. The sound and expressivity of the Philadelphia Symphonic Choir, so appealingly positioned on this fantastic corridor’s so-called “Conductor’s Circle” behind the orchestra, resonated completely from the opening pianissimo measures to the craze of the Dies irae.

The viewers appeared enraptured. Trying round me, I questioned if any of the opposite listeners had been listening to what I used to be listening to, simply over per week earlier than this terrifying election, when the mezzo-soprano lamented,

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

Quem patronum rogaturus,

Cum Justus sit securus?[What shall I, wretch, say?

Whom shall I ask to plead for me

When scarcely the righteous shall be safe?]

Photographs: Jeff Fusco